My first mistake on my first big day of riding, other than waking up too late, was leaving the specifics of packing the bike until the last moment.

Sure I had general ideas about where I might put things but it’s not until you start piecing the puzzle together do you realize that it’s not as easy it seems.

Adding to this, it was my first real overlanding trip and as most first-timers tend to do, I brought too much stuff. The need to start cutting gear became apparent after nearly 45 minutes of Tetris, but I wanted to wait until I knew what I didn’t need. I managed to get it all on there but I was heavy and cumbersome; not an ideal combination for a newbie.

My pre-dented metal panniers on the rear and waxed cloth tank bags on the front were packed with the heaviest gear and tools, a lockable steel top case behind the rear seat held lighter items, and my rear passenger seat was stacked with bags of clothes, food, maps, my tent, and assorted camping equipment.

Finally packed, I started up the 950cc engine to get it warm before departure, a beastly purr filling the cobbled streets. Unsure of whether I felt like a badass or a total poser in my unblemished riding gear, I managed to do the adventure-rider-hop as I hurdled my right leg over the saddle and gingerly slid between my tank bag and the duffels on the passenger seat. Feeling more like a piece of deli meat in a sandwich than a comfortable motorcyclist, I waved goodbye to Smith once I had worked out my wobbles and just like that, my ride through South America had officially started.

I excitedly road my thunderous KTM through the choked Bogotá traffic, being assertive but also finding the flow of the traffic. After what seemed like far too long, I finally broke loose of the city and found my way into the dense, jungled mountains and dangerously switch-backed Routes 50, 45, and eventually 60.

With Medellín being the other major Colombian city and, as the crow flies, not all that far away, I wrongly assumed that this major route would break from the two lane (one either way) system I knew most of the Pan-American to be. At just over 400km away, my ignorance of the speed of travel in the region was highlighted on this first leg. I did not make good time.

Getting Out of a Bribe

Shit-scared and sandwiched between transport trucks and buses, endless switchbacks and oncoming traffic stunted most passing attempts until finally the road opened up on a straight away and I, along with two other vehicles, gunned it around some slow movers. The rush of wind and speed excited the senses, a grin creeping across my face, the overhanging trees blurring into a connected tunnel. The exhilaration was short-lived however. A policeman in a reflective vest jumped into the road and frantically flagged me down.

Nervously, I pulled over to the police car but noticed the locals had been waved on. I immediately suspected they were going to squeeze me for a bribe. Play dumb, stay calm.

The policeman explained, in Spanish, that I was being pulled over for passing in a no passing zone. While my Spanish isn’t great, I understood what he was saying but didn’t let him know that. I told him that I only spoke English. Through hand gestures, more Spanish, and a couple of English words, the policeman once again explained that I had passed where I was not allowed. Again I pretended not to understand.

This time, the policeman sitting in the car, who seemed to be in charge, spoke up and said that I had a $300 ticket to pay and that I could either pay a lesser amount now or pay the full amount in town.

It was hard to deny understanding at this point because the other policeman spoke enough English to make his point clear and it was clearly a bribe they were after. But I wasn’t going to give in just yet.

I pleaded with them, stating I was a student with no money that had just borrowed a friends bike (the notarized letter proved it) and was visiting for a couple of weeks before returning to school. After reiterating my mostly false sob story, the policeman got visibly tired of me, let out an exasperated sigh and shooed me away.

It worked! I had gotten out of paying these pricks a bribe!

Too nervous to look back, I cautiously left the gravel and got back onto the highway, careful not to accelerate too quickly. It wasn’t until almost a mile down the road that I let out a celebratory “Wooo!” You just got out of your first bribe attempt. Nice work. Now focus on the road.

Don’t Ride at Night!

With such a late start, I knew I was going to break the cardinal overlanding rule of no night driving/riding. This rule was one of the first that Chris and Erin imparted on me. I broke it the first day.

With night encroaching and noway that I was going to make it to Medellín, I had to find another place to stay. The sunset faded to a deep darkness and I went to turn on my high beams. Click-click. Nothing. Just my dull day-runners. This isn’t good. This isn’t good at all.

With reduced light, I was forced to cruise slowly along the shoulder of the highway while trucks, buses, cars, and motorcycles raced passed. Angst, worry, and general fear for my safety became thoughts difficult to push away. What am I doing here? What was I thinking? I have no business being out here.

Just then, a local on a motorcycle noticed my plight, pulled up behind me and shone his lights on me. Encouraging me to keep going, he rode for miles while keeping me lit; eventually having to turn off for his destination but an act that I will soon not forget.

With more than three hours to go and enveloped in complete darkness, I realized that I just had to find a place to sleep for the night. With wild camping out of the question for a host of reasons, I kept up hope for a third rate hotel, a B&B, a truck stop, a developed campsite, a safe hut with a toilet; literally anything that wasn’t too sketchy. And then it came, the promised land, a second-rate resort themed around water and fake animals.

From the half dozen billboards along the highway, I gleaned that a mildly atrocious resort-hotel-motel-theme park had a baby next to the highway. Pulling into the parking lot, I realized my assessment was not far off. Fake animals dotted the surroundings of a laterally built motel, it’s brighter days decades ago.

The front desk staff were helpful and warm, welcoming the slightly frazzled gringo to their seemingly out of season resort. They even allowed me to email my family to let them know I was safe. As it was my first big day riding, I told my family I would let them know when I got to Medellín. The young man and woman working the desk were most understanding and for the second time in hours I experienced the unfortunately overshadowed Colombian reputation of exceeding hospitality and kindness.

With my bags officially plopped in my room, I turned my motorcycle jacket and pants inside out so that the sweat could dry. The overworked oscillating fan struggled valiantly against the thick, humid air, which thankfully had cooled off from the afternoon simmer.

While undressing for a much needed shower, a thumb-sized cockroach appeared above the headboard of the bed, seemingly out to inspect the next occupant of its abode. Swatting to shoo it away rather than squash it, I grumbled at the little disease vector but accepted it nonetheless. It wouldn’t be the last and I was too tired to care.

Freshly showered, I pointed the cobwebbed fan over the bed and splayed out to maximize air flow. Worn out from an intense day, I drifted off to sleep, content with the idea that I had made it safely through my first day; not something to be overlooked nor taken lightly.

The City of Eternal Spring

With only three hours to Medellín, I left late enough to avoid rush hour. A foggy ride gave way to the dramatic Aburrá Valley, the name derived from the indigenous Aburrean language. The highway rapidly showed improvement from the narrow, pock-marked path I come through with freshly tarred roads, multiple lanes and tolls, which were thankfully free for motorcyclists.

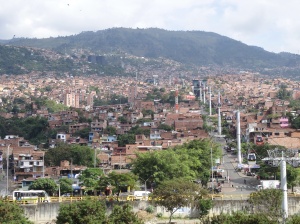

Traversing down the lush mountainside at a rapid rate, bustling between cars, trucks, and buses, I managed to sneak views of the deep valley below and the juxtaposition of civilization and natural foliage. Medellín, made up of millions of houses, shacks, apartments, and buildings smothering the landscape, looked to be carving out a slow amoebic growth, tightly wrapped by roads and jungle; at the ready to swallow up civilization the moment it stops.

Dropping further down, the barrios of the poorer population appeared first, followed by industrial businesses, commercial businesses, and eventually the wealthier area of town near the city center. Late morning traffic moved amicably with toots of car horns communicating rather than the more accustomed blaring of distaste that American commuters may experience.

There is a subtlety to honking/hooting in traffic. It is not just on or off. Light tapping can tell someone “Get ready for the green light” or “Hey I’m coming through the intersection.” On the other hand, laying on the horn for an uncomfortable period of time is likely to send that message that “I think you are a wretched ghoul of a human.” While aggressive jabs of your horn will likely let the receiver know that they are in fact “a complete inbred, devoid of sound logic, and should likely drive into heavy, stationary objects.” The nuances go further but this is a good starting point.

Meeting Another Adventure Rider

Arriving at Hostal Poblado Park a day later than initially planned, I was greeted by the front desk attendant, Eddie, a British man of Nigerian descent. In his late 20s and sporting a posh, Queen’s English accent, Eddie was much warmer than yesterday on the phone when I called to let the hostel know I would not make it on time. After a short chat about what I was doing in South America, Eddie got notably more excited and explained that he will be around all week if I needed anything.

After 3 separate trips hauling all of my bags and panniers to the safety of the 8 bed dormitory on the second floor, I was greeted with a moment of much anticipated respite. With my feet still on the floor, I flopped back on my bottom bunk and let out an exultant sigh. You just finished your first leg! You did it. You didn’t die. You can do this.

Knowing very little about Medellín other than what I had skimmed through in my Lonely Planet guidebook, I had no heightened expectations and looked forward to relaxing after a busy first week. The first priority was arranging a service for the motorcycle at the KTM dealership. Chris and Erin, who had sold me the bike, told me that it needed a basic service and that there was a good KTM mechanic near Hostal Poblado Park, which they had also recommended.

Arranging a bike service for tomorrow, I spent the rest of the day writing in my journal and relaxing in the hostel. Leaving only to get food from the supermarket, I returned on foot to see another adventure touring motorcycle, covered in flag stickers, sitting right next to mine. Excited to see another adventure rider, I wondered who he or she could be.

Entering the rectangular, communal kitchen, a blonde, European man in his mid-30s was working away on his laptop. Looking up with a smile and a nod, I reciprocated the gesture and went about preparing the spaghetti and red meat sauce extravaganza I had planned for dinner; my first time cooking since before leaving home.

After a few minutes of silence, the other man asked “Is that your KTM downstairs?” A thick German accent encapsulating the sentence.

“Yes it is. Is that your Kawasaki KLR 650?” I asked.

“Yes! I bought it in Canada and rode it down from Alaska and I’m hoping to go all the way around the continent,” responded the German, with a calm and confident smile.

“Wow! That’s very cool; you’re doing what I want to do but in reverse! My name is Guy. What’s yours?” I said, sticking my hand out to shake his.

“Martin, nice to meet you!” the German said, gripping my hand and issuing a firm and friendly shake.

While we prepared out food, Martin and I chatted about our backgrounds. I asked the genial German about his trip, looking to glean as much as I could from the exponentially more experienced adventure rider. He explained that after working in Vancouver, B.C. for a year, his itch to ride the entire Pan-American became overwhelming. He bought the KLR 650 I saw next to mine and set off for the Arctic Circle before turning around and heading South. Martin went on to give anecdotes and enthralling stories, including the time his motorcycle was stolen by drug dealers in Mexico.

For 10 minutes, Martin acted out the almost impossible story of his unfortunate theft experience that included a high speed chase in a taxi and a ludicrously long 6 week search for his missing bike. He went on to explain that after walking around every neighborhood in the town, he found the bike. It had been poorly repainted and was missing the panniers, but it was unmistakably his with various, distinct aftermarket accessories he had installed personally.

Gathering a platoons-worth of well armed police, Martin returned to the location of the motorcycle. Acting out how the police were stacking up, rifles at the ready, I was expecting to hear of the ensuing chaos and violence.

Instead, Martin exclaimed “The police chief and main suspect hugged each other as soon as he opened the door! They knew each other! And even though I had the paperwork to show that it was my motorcycle, I had to pay $500 to get my own bike back!

And yet despite this, Martin maintained “It is still my favorite country so far and I can’t wait to go back.”

Exploring Medellín

With my bike serviced and riding like a dream, it was time to see the city. Martin and I decided to go out exploring together as it was safer and we were enjoying each others company.

Once the epicenter of the cocaine trade and home of Pablo Escobar, Medellín once had the reputation of the most murderous city in the world. Today it’s a bustling metropolis of 3 million people with the only metro system in Colombia, relaxing parks, and friendly people. With that said, the city is not without risk and we knew that you still had to be careful about where you went.

The infamous cartel leader and drug smuggler, Pablo Escobar, was and is still regarded fondly by some for his generosity to the poor; he once even offered to pay off the public debt of Colombia. However, his legacy of murder, drugs, and fear is not forgotten more than 20 years after he was famously gunned down on a Medellín rooftop in December 1993. Admittedly, I felt strange about having any desire to see the grave of such a ruthless tyrant. Is this immoral or unethical? Is it okay to just see something out of curiosity and nothing more? At least I’m not paying money for it.

While there are formal tours that I heard are interesting, Martin and I decided to save a little money and just visit his grave in the well manicured Cemetario Jardins Montesacro.

Tastefully elaborate, we found Escobar’s grave, alongside those of members of his family. For me, there was no special reverence or feeling it created other than here it is and a lot of people died as a result of this guy, I hope society is better without him.

As a patron, fan, and general appreciator of art, I was excited for the Museum of Antioquia. Each with a little plastic cup of freshly squeezed orange juice from the local vendor, Martin and I strolled to the west end of Plazoletas de las Esculturas early the next morning. We were there to see the Museum of Antioquia which houses pre-Hispanic, colonial, modern art, and work by Colombia’s favorite son, Fernando Botero.

As we approached the museum entrance, Botero’s largest bronze pieces began to express their detail, magnitude and playful shapes while laying out long looming shadows caused by a narrowly risen sun.

Inside, the thoughtfully laid out museum presented us with a dizzying spectrum of powerful art pieces. Botero’s painting of Pablo Escobar’s rooftop death struck me as more powerful than his grave the day before; the graphic nature of his death painted rather than read about.

The museum went on to show more dramatic pieces of the plight that much of the average population was facing during the turbulent cartel wars of the 1990s. Other pieces showed playful modern expressions of indigenous design and color schemes. Others were a complete psychedelic expression of genius.

As art museums tend to, I left hours later, drained but inspired and humbled by centuries of artistic expression. Tough times may make tough people, but tough times also make incredible art. Colombia shows it is no exception.

Feeling the effects of the previous nights rum and cokes and late night socializing with Martin and Eddie in Parque Lleras, I rustily arose from my bunk and staggered to the kitchen for a breakfast of instant coffee and scrambled eggs. With our bearings better greased, Martin and I walked to the metro. Expecting disorganized apathy, we were instead humbled by how new, efficient, and functional the rail system all flowed.

Zipping along to the north of the city, Martin and I aimed for one of the newly constructed cable cars that dot Medellín’s hillsides. Not long passed before the metro came to a stop and conveniently dropped us at the first cable car; an initiative to connect the poorer barrios on the side of the mountain down to the economic zones.

Boarding the modern cable car, the doors suctioned shut and we burst out into the sunlight, momentarily blinding us before adjusting our new environment. Hovering just above the barrios, we crept up and up, peering into the lives of ordinary Colombians going about their business. Some areas looked notably sketchy while others serene. Even though it felt a little like floating along at an amusement, the ability to peer into the lives of the ordinary citizens without being a distraction yourself, was a blessing I hadn’t considered.

At the top, we boarded another cable car bound for Parque Arvi, a nature reserve on the backside of the mountain. Rather than riding over barrios, the terrain changed to a Jurassic Park-like existence below with giant trees, ferns, and a depth of jungle I wasn’t expecting.

With last nights rum starting to push its way to the surface of our pores, Martin and I decided today was not the day for hiking or renting bicycles. Instead we ate an overpriced meal at the cafe, enjoyed the view of nature, and people watched, while people watched us, two blonde men in a Latin America, an uncommon sight I quickly learned.

Saying Goodbye Sucks

Leaving starts feeling like a bad idea when you realize it’s time to go. With still so much to see and do, I felt that I had only just started experiencing a city that was soon becoming one of my favorites.

Eddie, the Englishman, had been a great introduction to Medellín through his knowledge of the city and his social circles. Adding to that, Martin and I had formed an immediate friendship within days and the idea of saying goodbye already was frustrating and mildly painful. But that is travel. I was going north to the Caribbean coast but that’s where he had just come from. We were going in opposite directions.

“We will see each other again, I know it” said Martin, giving me a big hug and pat on the shoulder.

“I have a feeling we will too, I just wish it was sooner” I responded with a smile.

“Well the road gives us strange twists and turns, so you never know, we could be seeing each other sooner than we realize!” exclaimed Martin.

“Let’s hope so, friend” I said before hopping on my motorcycle, hooting my little horn, and once again, leaving hours later than I planned. Why is this the way you are? This is already a 12 hour ride as it is, why make it harder?

Up next, Chapter 3: The North Coast of Colombia

Start this journey from the beginning: Introduction